A New Economic Development Strategy to Reduce Inequality by Income, Race, Education, Gender, and Geography

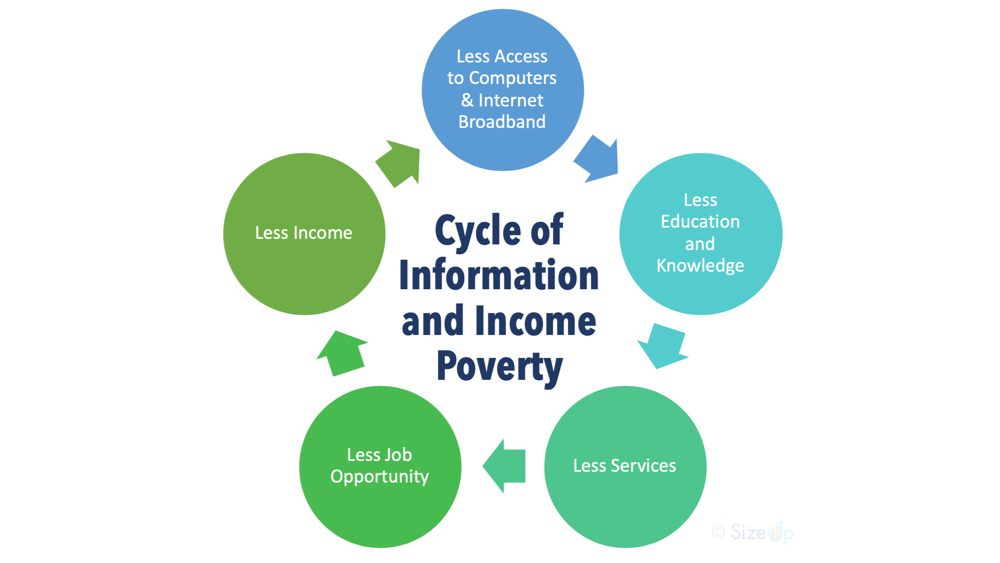

A lack of access to technology hurts local economies. Inequitable access to the Internet and computing devices creates a “digital divide” which disadvantages marginalized populations including the poor, racial minorities, women, and the less educated. Structurally, information poverty and income poverty create a vicious cycle.

Today, expansive access to computer devices, high speed internet, and data/information is essential to thriving economies. Technological competence combined with digital access is also defining economic winners. Tech “have nots” find themselves economically disadvantaged. By implementing programs that specifically address the technological divide in their communities, economic developers can increase wealth and economic activity across their area’s entire population.

DIGITAL DIVIDE

Technology and the Internet have been positioned as a utopian path to digital democracy and a level playing field. However, this egalitarian ideal does not align with the bifurcated reality. Instead, technology, data, and the Internet have disproportionately benefited those who are already the most privileged. Instead of equality, it has enabled greater inequity. Not everyone has, uses, or knows how to use technology.[1] Effective targeting of economic development assistance to bridge the digital divide requires a quantified understanding of who is in need.

Income

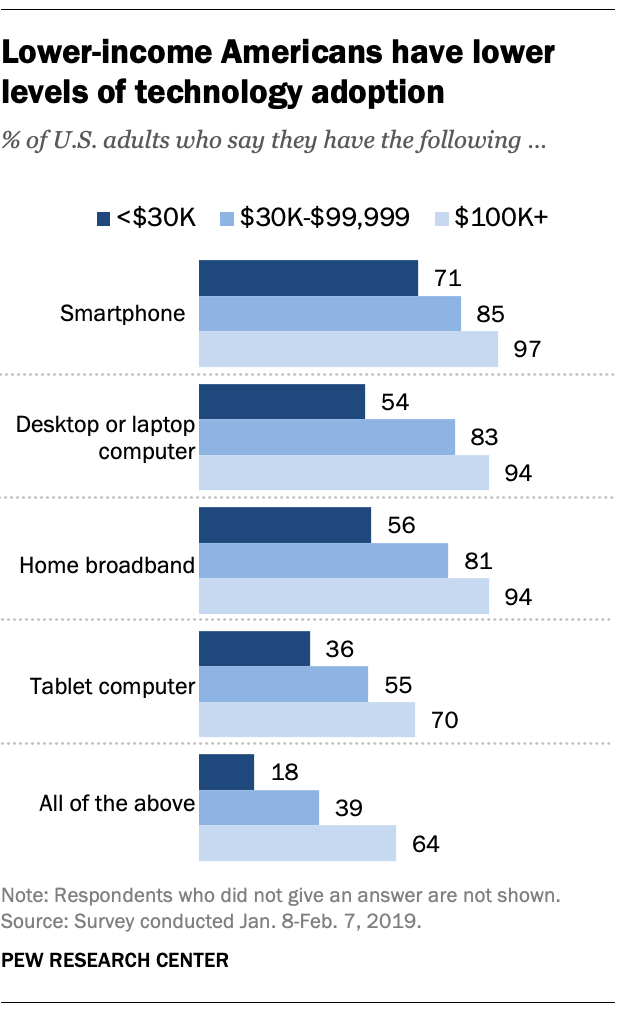

The digital lives of lower- and higher-income Americans is very different. “Roughly three-in-ten adults with household incomes below $30,000 a year (29%) don’t own a smartphone. More than four-in-ten don’t have home broadband services (44%) or a traditional computer (46%). And a majority of lower-income Americans are not tablet owners. By comparison, each of these technologies is nearly ubiquitous among adults in households earning $100,000 or more a year.”[2]

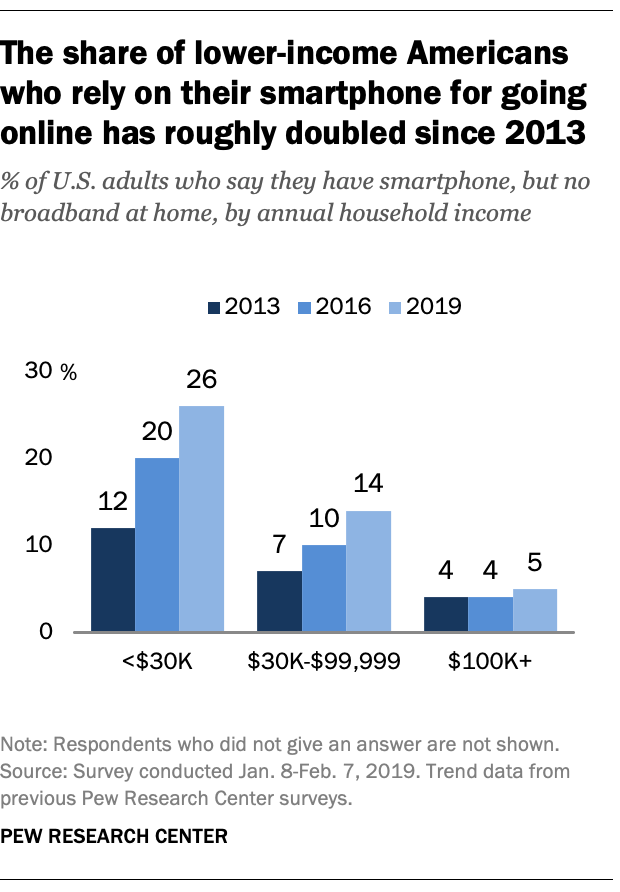

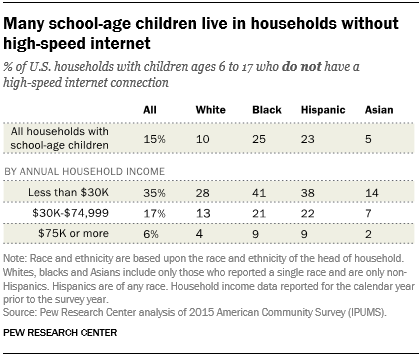

Higher income people are more likely to have multiple devices to go online whereas many lower-income people have to rely on their smartphones to go online, which is classified as being “underconnected”.[3] This forces low-income people to use their phones for tasks that are typically reserved for large screens such as applying for jobs online. This also impacts students because, 35% of lower-income households with school-age children did not have a broadband internet connection at home.[4] There are also impacts of continuous access uncertainty as “a third of families with mobile-only access quickly hit the data limits on their mobile phone plans and about a quarter have their phone service cut off for lack of payment.”[5]

Geography

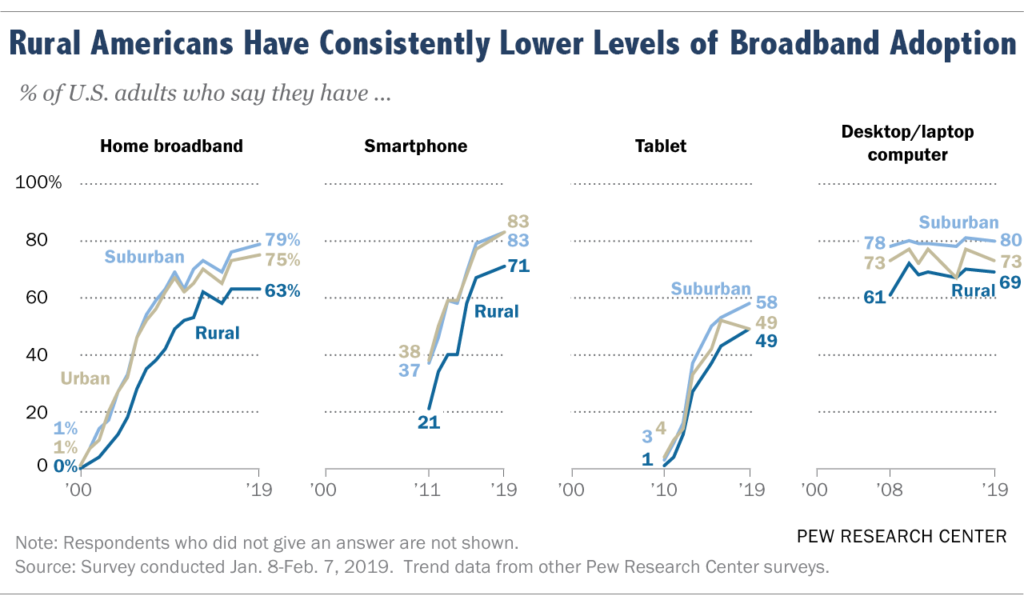

Rural residents have made gains in closing the gap with digital technology but are still 12 percentage points less likely than Americans overall to have home broadband. They are also less likely to own a smartphone, tablet, or desktop/laptop computer than suburban or urban adults.[6]

15% of rural adults never go online, compared with 9% living in urban communities and 6% who live in the suburbs. Nearly one-quarter of rural residents say that getting access to high speed Internet is a problem in their community. Substantial areas of rural America still lack the infrastructure needed for high-speed internet, and the access these areas do have tends to be slower than that of non-rural areas.[7]

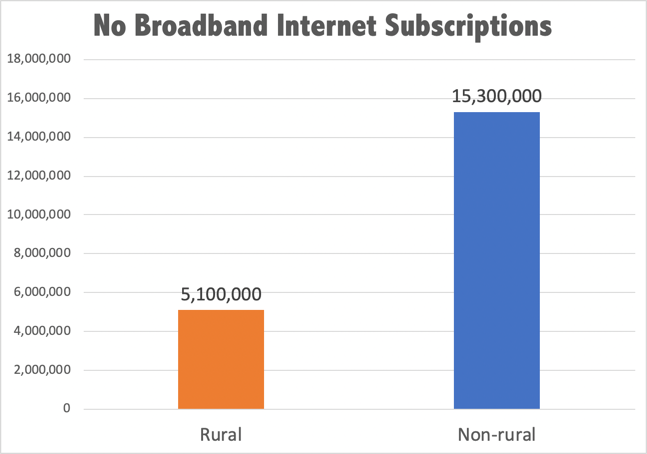

As troubling as rural adoption of broadband is, there are three times (15.3MM vs. 5.1MM) as many urban households unconnected to broadband. Urban adoption is a factor of consumer adoption. More than geography, a larger driver of non-adoption is the household costs of monthly broadband fee and the expense of a computer. This shows that even if a household has the physical infrastructure to access broadband, it won’t if it can’t afford to use it.[8]

Race

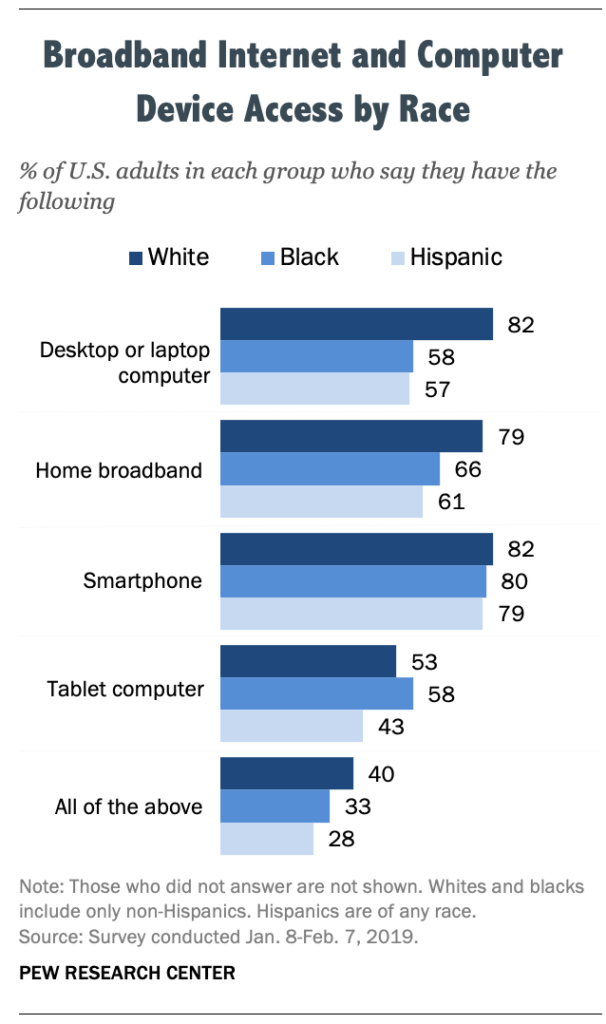

Black and Hispanic adults are less likely than Whites to own a traditional computer or have high speed internet at home. 82% of Whites own a desktop or laptop computer, compared with 58% of Blacks and 57% of Hispanics. 79% of Whites have broadband at home, compared to 66% of Blacks and 61% of Hispanics.[9]

Smartphones are a key method for Blacks and Hispanics to access the Internet, information, and looking for work. However, Blacks, Hispanics, and lower-income smartphone users are about twice as likely as Whites to have canceled or cut off service because of the cost. This disruption of access can be devastating because mobile devices play a larger role for Black and Hispanic people as 25% of Hispanics and 23% of Blacks are “smartphone only” internet users, which means they own a smartphone but lack traditional home broadband service. 12% of Whites are “smartphone only” by comparison.[10]

Education

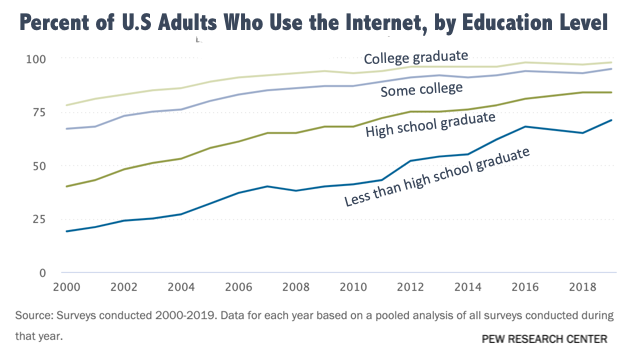

The less education a household has, the less likely the home uses the Internet (at all)[11] or has a computer.[12] Only 71% of people with less than a high school education use the Internet compared to 98% of college graduates.[13]

If a household is less familiar with computing devices – even smartphones or tablets – they are less likely to know how much valuable information is available online, much of which is free. Non-adopting parents may also not realize how important the Internet has become for students, especially in underperforming schools.[14]

Those without Internet services are more likely to be heavy users of government services and may be unaware that many of those services are online. In addition, for those that have never been online or spend less time online, they may not be aware of “opportunities broadband offers for job skills, health information, smarter shopping, civic engagement, or using e-government services as an alternative to the costly process of visiting government offices in person.”[15]

Jobs

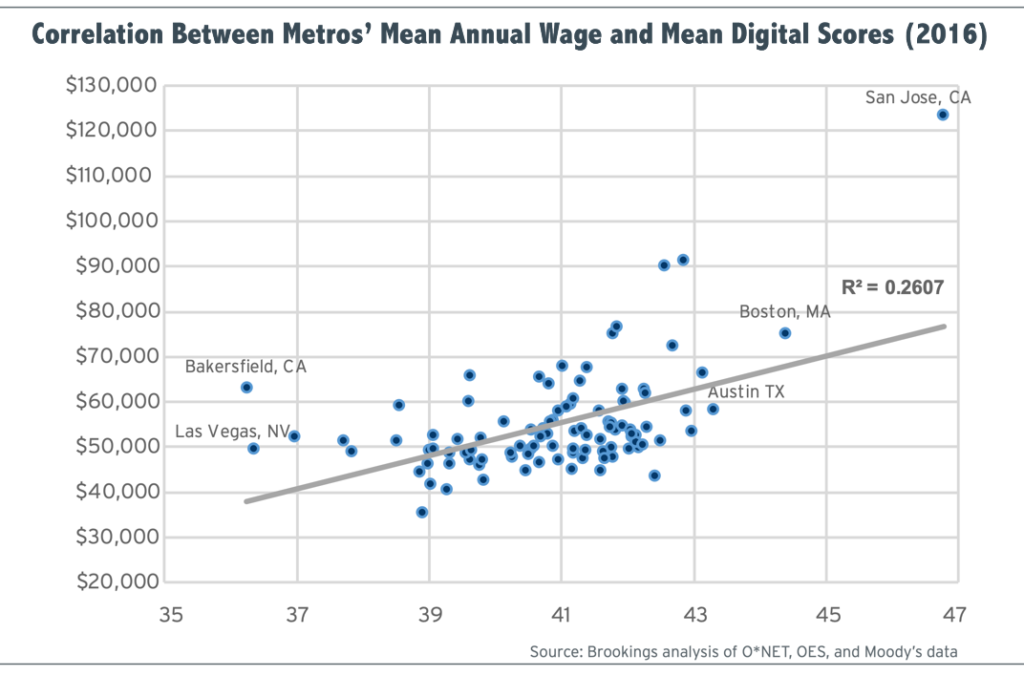

In 517 of 545 US occupations the use of digital skills has increased 57%, on average, from 2002 to 2016. Jobs with digital skills are growing, pay higher wages, and are more resilient.

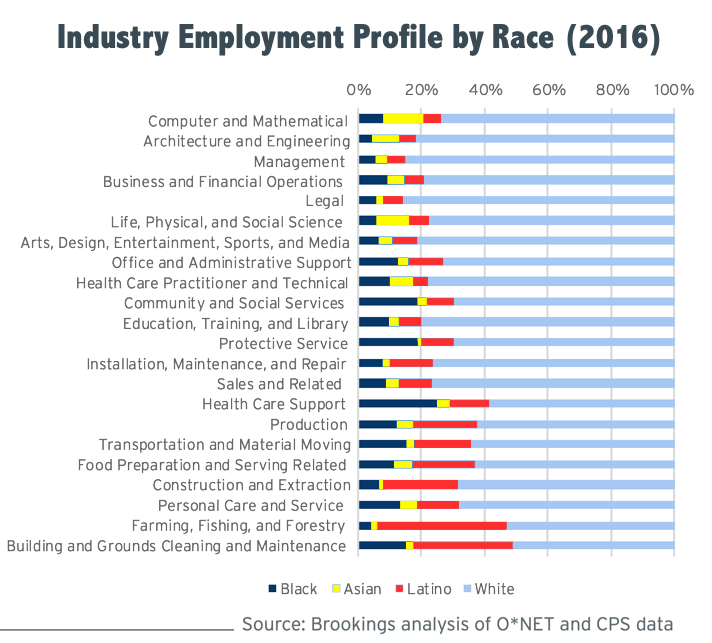

Whites remain overrepresented in high-level digital occupations such as engineering and management as well as medium-level digital areas such as business and finance, the arts, and legal and education professions. Blacks are overrepresented in medium-digital occupations such as office and administrative support, community and social service, and low-digital level jobs such as transportation, personal care, and building and grounds maintenance. Hispanics are significantly underrepresented in high-level digital technical, business and finance occupational groups, and somewhat underrepresented in medium-level legal, sales, and education jobs.[16]

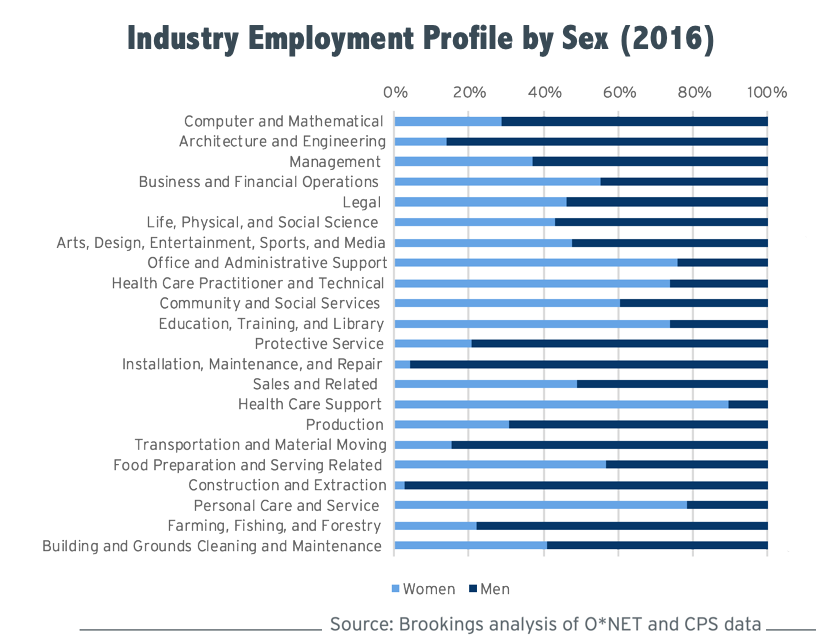

Men continue to dominate the highest-level digital occupations, such as computer, engineering and management fields. Women represent about three-quarters of the workforce in many of the medium-digital occupational groups, such as health care, office administration, and education.[17] The gap of women working in the tech industry which creates digital products and services is significant. “Facebook, Google, and Apple have 17%, 19% and 23% women in their technology staffs, respectively. Multiple surveys, such as the “The Elephant in the Valley,” have documented systematic discrimination against women.”[18]

CYCLE OF INFORMATION AND INCOME POVERTY

As research from the US Dept. of Housing and Urban Development explains, “As information, services, and resources increasingly move online, digital inequality has come to both reflect and contribute to other persistent forms of social inequality. Disparate access to the Internet and digital devices corresponds closely with longstanding inequalities in income, education, race and ethnicity, age, immigration status, and geography. At the same time, the negative consequences of being underconnected are growing, and researchers and policymakers are increasingly concerned that underconnection is fueling other socioeconomic disparities. Indeed, Internet access, and particularly broadband Internet access, has become an important tool for taking full advantage of opportunities in education, employment, health, social services, and the production and dissemination of knowledge and digital content. Yet those who are most in need of social services are often least able to get online to access those services, and low-income children — who are four times less likely to have access to broadband at home than their middle- and upper-income counterparts are particularly vulnerable to the long-term detrimental effects of constrained access to technology-enriched education. These trends suggest that digital access will play an increasingly central role in socioeconomic inclusion.”[19]

Limited access to the internet and computing devices (as the previous data shows is unequal by income, race, education, and geography) is a barrier to becoming digitally skilled and a long-term barrier to the economic opportunities of the better-quality jobs that increasingly require digital skills.

This phenomenon is having a growing impact on local economies because areas with more digitally savvy residents earn higher average wages. Communities that do not increase information access through the Internet and computer devices risk geographic economic exclusion if the highest paying jobs and greatest economic output are created in tech-savvy regions of the world, while other regions are left behind.

WHAT ECONOMIC DEVELOPERS CAN DO

Access to broadband internet, appropriate computer devices, and data information are fundamental to participating in the modern economy. Economic developers have an important role to play in alleviating information poverty to enable economic opportunity and growth. The following are a few ways that the profession can do this so that communities are not condemned to information poverty.

1. Public Broadband

Government agencies are delivering public Internet service which, in many cases, is both faster and cheaper than corporate Internet Service Providers. These systems can guarantee Net Neutrality and offer competition in areas in which private providers functionally have a monopoly or duopoly. “Cheap and excellent broadband is a tool for equity, but also for economic development.”[20] Citywide broadband access is important for enabling equitable access to all residents wherever they are located and not just in public hot-spots. 17% of teens say they are often or sometimes unable to complete homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection.[21] So many public serving agencies can benefit from public broadband including education, economic development (for all the reasons mentioned and because freely accessible broadband is a competitive location advantage for business startups and attraction[22] and because customers spend more money at businesses with free WiFi), tourism, and disaster response. Because this is an investment in business success for companies and employees today and in the investment in future workforce in the schools, EDOs are well positioned to make the economic case for the investment.

2. Data for Entrepreneurs

Small businesses and prospective entrepreneurs face information access obstacles that limit their ability to get quality information to operate, improve, or start their business. Whereas large or well-funded businesses may have technical staff and a digital infrastructure to acquire and manage business intelligence and research, small businesses and new entrepreneurs are less likely to have the digital skills to access this information and are likely to be excluded because of their inability to afford it. In today’s information economy, businesses without access to information are at a material disadvantage which can result in their failure. To level the business playing field, economic development organizations are increasingly providing open access on their websites to industry market research using SizeUp. Local businesses use this information to make data-driven decisions to improve their businesses and aspiring entrepreneurs use it to test and validate their business plans and assumptions. By doing so, economic developers can mitigate the information insufficiency that plagues entrepreneurs, and specifically those that are from information poverty populations including women, African Americans, Hispanics, and the poor.

3. Small Business Assistance

Small businesses create the overwhelming majority of all net new jobs. Locally owned businesses also contribute more locally through a higher local economic multiplier. Although 85% of US businesses are owned by White men, by focusing programs and assistance toward small businesses EDOs are also able to target the growing share of minority owned businesses. The rate of minority business ownership in 2012 was 14.6 percent, compared with 11.5 percent in 2007.[23] Economic developers support small businesses in many ways including Business Retention and Expansion programs, Economic Gardening, and delivering free access to industry market research and business intelligence. Small businesses experience information deficiency so providing them with greater amounts of information and data is needed to help level the business playing field.

4. Computers and Training

A lack of high-speed internet and the types of larger-screen computer devices typically used for job searches harm employment opportunities for job seekers. Searching and applying for jobs is increasingly moving online through job posting websites and online submissions for jobs. Over 80% of Fortune 500 companies require online job applications.[24] Desktop versions of websites frequently have more features and information than the mobile device screen versions of webpages. This disadvantages underconnected people who are smartphone-only. Also, a research study from the University of Southern California showed that computer access and “boot camp” training can improve job prospects for low income residents, almost all African American or Latino, and over half of which had not completed middle school.[25] “Adult participants took advantage of their newly acquired computer skills and put them to use towards submitting resumes and filling out employment applications through online sources at significantly greater rates than non-participants.”[26] The profession of economic development is adept at making calculations to justify multi-million dollar financial incentives for job-creating companies coming into a community. One million dollars could buy 4,000 Chromebooks (even at retail prices) which could be provided to marginalized residents of a community.

5. Funding

Programs funded by government and economic development can measure how well they serve those which are in most need. This can be accomplished by tracking both who is served and the impact of the services provided. By simply measuring the income, race, sex, education, age, and other demographic characteristics, economic development organizations can quantify how effective they are at serving marginalized populations.

Expanding Economic Development

Economic developers have focused their work on traditional programs such as real estate development and reuse, business retention and expansion, business attraction, marketing, tourism, and other longstanding practices. However, the barriers to positive economic development are changing as the economy is evolving, with much of the change emanating from the transformative impact of technology and information. For the economic development profession to keep up with the times and remain relevant it must transition its time, programs, and budget toward the new opportunities to enable economic development through the reduction of information poverty.

Please share this article so more people will know about this information and strategy.

FOOTNOTES

[1] “Haves, Have-Nots, and Have-to-Haves: Net Effects of the Digital Divide,” by Elory Rozner 1

[2] “Digital divide persists even as lower-income Americans make gains in tech adoption” by Monica Anderson and Madhumitha Kumar. Pew Research Center. May 7, 2019.

[3] “What Low-Income Students Miss When Their Only Internet Access is Through Their Phone,” by Crystle Martin, University of California, Irvine. Center for Digital Education, GovTech. February 11, 2016.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “Smartphones help blacks, Hispanics bridge some – but not all – digital gaps with whites,” by Andrew Perrin and Erica Turner. Pew Research Center. August 20, 2019.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Analysis: Digital Divide Isn’t Just a Rural Problem,“ by John B. Horrigan, Senior fellow at the Technology Policy Institute. The Daily Yonder – Keep It Rural. August 14, 2019

[9] “Smartphones help blacks, Hispanics bridge some – but not all – digital gaps with whites,” by Andrew Perrin and Erica Turner. Pew Research Center. August 20, 2019.

[10] Ibid.

[11] “Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet” Pew Research Center. Data is for 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/

[12] “Digital divide persists even as lower-income Americans make gains in tech adoption” by Monica Anderson and Madhumitha Kumar. Pew Research Center. May 7, 2019.

[13] “Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet” Pew Research Center. 2019.

[14] “Cities, not rural areas, are the real Internet deserts,” By Blair Levin and Larry Downes, The Washington Post. September 13, 2019.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Digitalization and the American workforce,” by Mark Muro, Sifan Liu, Jacob Whiton, and Siddharth Kulkarni. Brookings Institute. November 2017

[17] Ibid.

[18] “There’s a Gender Gap in Internet Usage. Closing It Would Open Up Opportunities for Everyone,” by Bhaskar Chakravorti. Harvard Business Review. December 12, 2017. No more than a quarter of U.S. computing and mathematical jobs are held by women, consistent with the data that around 26% of the STEM workforce in developed countries is female. In developing countries, those differences are even greater.

[19] “Evidence Matters: Digital Inequality and Low-Income Households.” HUD User Office of Policy Development and Research. US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Fall 2016.

[20] “Public Internet: A great idea whose time has come.” By Matt Reed. Inside Higher ED. June 26, 2020

[21] “Nearly one-in-five teens can’t always finish their homework because of the digital divide,” by Monica Anderson and Andrew Perrin. Pew Research Center. October 26, 2018

[22] “Discover how communities are investing in their own Internet infrastructure to promote economic prosperity and improve quality of life,” Institute for Local Self Reliance.

[23] “Demographic Characteristics of Business Owners,” by Jules Lichtenstein. US Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy.

[24] “FCC Chairman Announces Jobs-Focused Digital Literacy Partnership Between Connect2Compete and the 2,800 American Job Centers.” By Jordan Usdan and Kevin Almasy. July 23, 2012.

[25] “Computer usage and access in low-income urban communities,” By John Wihbey. Journalist’s Resource. August 19, 2013. “Computer Usage and Access in Low-Income Urban Communities,” a study from researchers at the University of Southern California, provides some insights into how computer access and computer “boot camp” training can impact job prospects. “A group of residents living in the Watts district of South Central Los Angeles — almost all African-American or Latino — was given access to computers through the Computers for Families program. More than three-quarters of participants reported household earnings of less than $1,000 per month, and 44% reported having no income. More than half had not completed middle school.”

[26] “Computer usage and access in low-income urban communities,” by J.C. Araque, R.P. Maiden, N. Bravo, I. Estrada, R. Evans, K. Hubchik, K. Kirby, and M. Reddy. Computers in Human Behavior, Volume 29, Issue 4, July 2013, Pages 1393-1401

[27] “Break the Cycle: Tackling Information Poverty as a Means of Eradicating Income Poverty,” International Federation of Library Associations. 16 October 2018

[28] “Smartphones help blacks, Hispanics bridge some – but not all – digital gaps with whites,” by Andrew Perrin and Erica Turner. Pew Research Center. August 20, 2019.